Programming Language Documentation Shootout

Introduction

The idea behind this post began as a rant, but I decided to revive my blog and expand on it. TL;DR: In my opinion, documentation is an integral part of programming language design.

People that know me know that I love writing code in multiple (some times unconventional, some times esoteric) programming languages, as well as comparing features of each language. They also know I love to flame sometimes, while I tend to show a lot of favoritism towards specific languages, so please do not be offended by whatever I might say. I always target languages and software, never people :)

As a multilingual guy, I tend to notice different things than most people:

- Features that behave differently in different languages (e.g. functional languages have inclusive ranges, procedural languages have exclusive ranges, making Ruby a functional language).

- I tend to favor design patterns and coding styles that work in multiple languages.

- I tend to see details most people ignore:

- Python not having a

file.read_to_stringfunction that reads a whole file to a string. - Ruby not having a

CSV.writemethod that writes a whole csv to a file. - .NET having the worst possible API to invoke external commands.

- Python having classes named with lowercase first letter inhibiting the use of local variables such as

set,stringetc. - How each language names its standard datatypes and how little sense they make. E.g. C#

Listand C++vectorbeing resizable arrays… Really, only F# got it right, calling it…ResizeArray!

- Python not having a

Today, I am going to do a multilanguage shootout on how each language handles documentation.

Let’s make something clear; I won’t talk about application documentation. I won’t talk about internal documentation (which I consider a managerial decision, not a technical one, since its cons are purely financial) but about public library documentation. What a developer sees when he/she tries to do something in a language. How easy it is for a developer to make changes to a production application and not just play with a library.

Is this really part of the design of a language? Before learning Rust, I would probably be sceptical. Now, read further and decide for yourself!

I will use three languages: Python, Ruby and Rust. I chose them because I think they have three distinct ways of showing documentation. There are other interesting candidates, such as C# (MSDN) and Java, but this post will get really long anyway, so I will refrain from including them. Also, I will talk about both standard library documentation and third-party library documentation.

To spoil the outcome, I will tell you what to expect of each language:

Standard Library:

- Expect Python to have large blobs of text that tell you stories. Expect pages littered with examples, with most things being unclickable. Documentation is not datatype-centric; you can’t expect clicking the return type of a function to bring you to a page containing only this type and its methods. Also, expect no sidebar to have an overview and navigate between classes.

- Expect Ruby to have a large page per class that has many examples, and is navigateable with a sidebar. Expect to have to do a lot of ctrl-f that, unlike python, will lead you to answers.

- Expect Rust documentation to be well maintained, navigateable, highly consistent and eye friendly. Expect to be able to collapse/expand the free text and the examples, allowing your eyes to do random access on the information they get.

Third-Party Libraries:

- Honestly, I am frustrated. Python documentation is a marketing tool. It does not try to document anything; each library tries to sell itself. You have to click multiple links before reaching the “real” documentation. There exist major inconsistencies in the appearance of different libraries. Python documentation relies heavily on tutorials and quick start guides, which are cluttered between pages.

- Ruby is self documenting. There have been times I had no access to the internet, did a

foo.methods.find { |x| x =~ /keyword/ }, and it worked. Jokes aside, expect navigateable large page documentation. Also expect inconsistency in the look and feel. Expect frustration if trying to search how to do something Ruby-on-Railsy (e.g. connect to a database) when you are not using Ruby on Rails ($!&!$@@!$). - Ironically, Rust follows the principle of least surprise: Expect the same look, feel and usability as the documentation of the standard library.

First example: Standard Library

Okay, okay, enough. Let’s start with something simple. Let’s check the standard library. Imagine we have to do something that needs a couple of datatypes. Let’s see how sets work.

Python

First of all, Python. Let’s search for the set documentation in our favorite search engine. If we succeed in finding the correct documentation and do not fall in stackoverflow questions, blog posts or w3schools (seriously WTF, I did not expect that)…

Great, this is a large blob of text with all std datatypes in the same page, with an anchor to both set and frozenset. Anyway, we can see two classes, set and frozenset. We can see a couple methods. Everything is there. Although the unnecessary use of bolds, large typesets and whatnot hurts my eyes.

Ruby

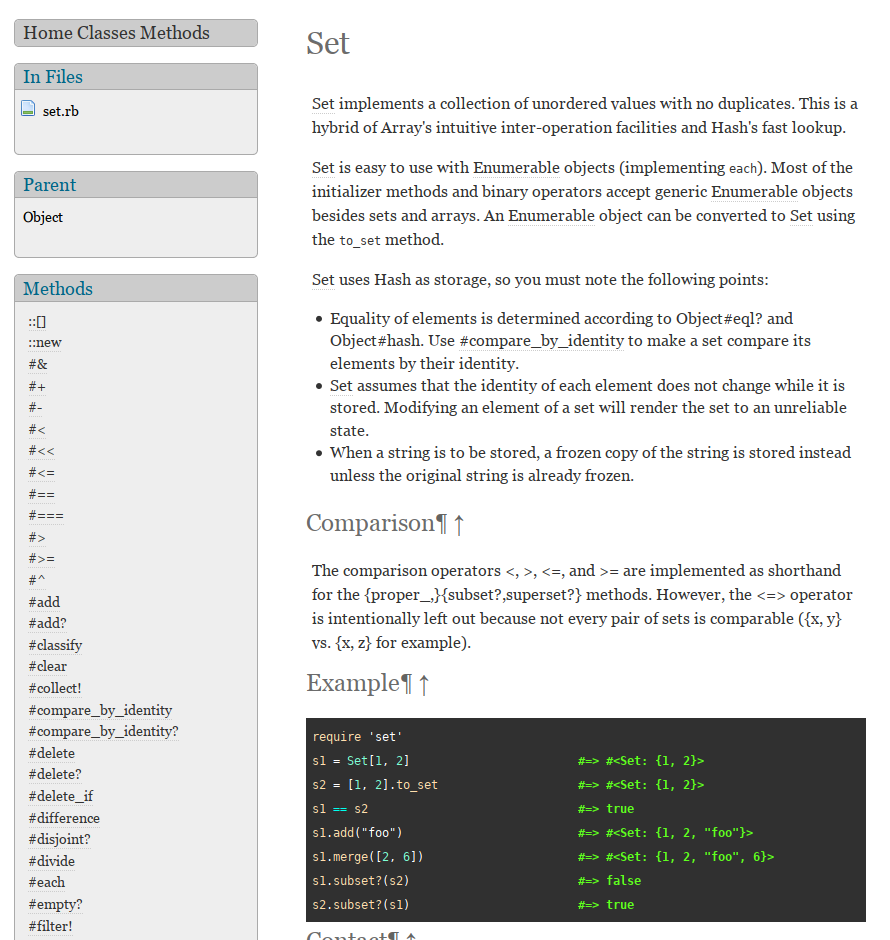

How does Ruby fare? Let’s see here.

Another blob of text. But, this time, we have a sidebar. And, more importantly, this page contains documentation only for the Set class. Which means that ctrl+f is guaranteed to take us somewhere useful, and not in a completely different datatype…

Rust

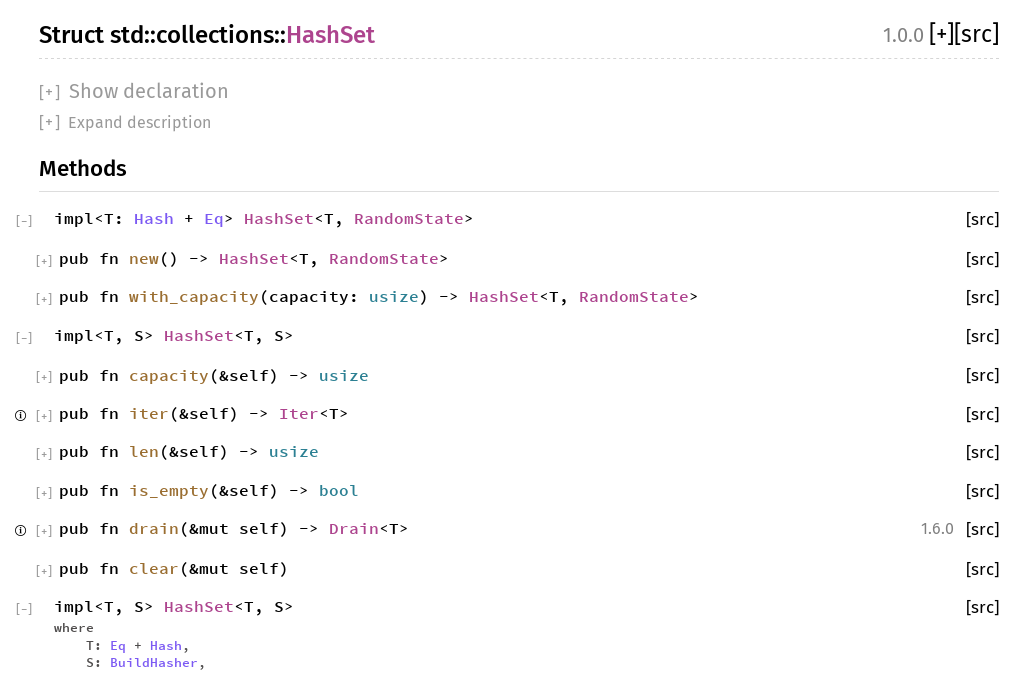

And finally, for Rust, this is what I call a proper documentation. (After pressing the [-] button, which I think should be collapsed by default).

This is the documentation that will be useful to a newcomer (since it has examples on every method, which can be collapsed/expanded) but also to someone adept at the language. In contrast to Python and Ruby, I can do random access on it - it is obvious at a glance what a method might do and what it might not, just by reading its name and type signature. And I can navigate where I think I will find answers. It is obvious if I am looking at a struct or a module, and for each module I can easily find all structs, all enums, all submodules. No, try it. I urge you to click on the collections part of std::collections and navigate the submodules.

Second Example: REST POST call

We want to do a REST POST call. To make it a little more interesting, we want to use SSL without verifying the certificate (yay, security!), since this is rarely found on the first example.

Python

I will begin with the “easiest” language, Python. I believe the state of the art library is requests. Let’s open the documentation of requests.

Behold, the power of requests! The power of having a car with both gas pedal and brakes! Sorry, couldn’t help myself :)

Where is the API documentation? Since Python documentation is inconsistent, we need to read the whole page to find it. There is an Introduction, an Installation (seriously, why is this even a topic in 2020), a Quickstart (cool, but I know exactly what I want to do), Advanced Usage and a Developer Interface after scrolling to hell and back.

You might argue that I am ranting for no reason, since I have not opened the documentation yet, but the landing page. But the url says readthedocs.io. It doesn’t say requests.io or github.io. So I expect to see the documentation.

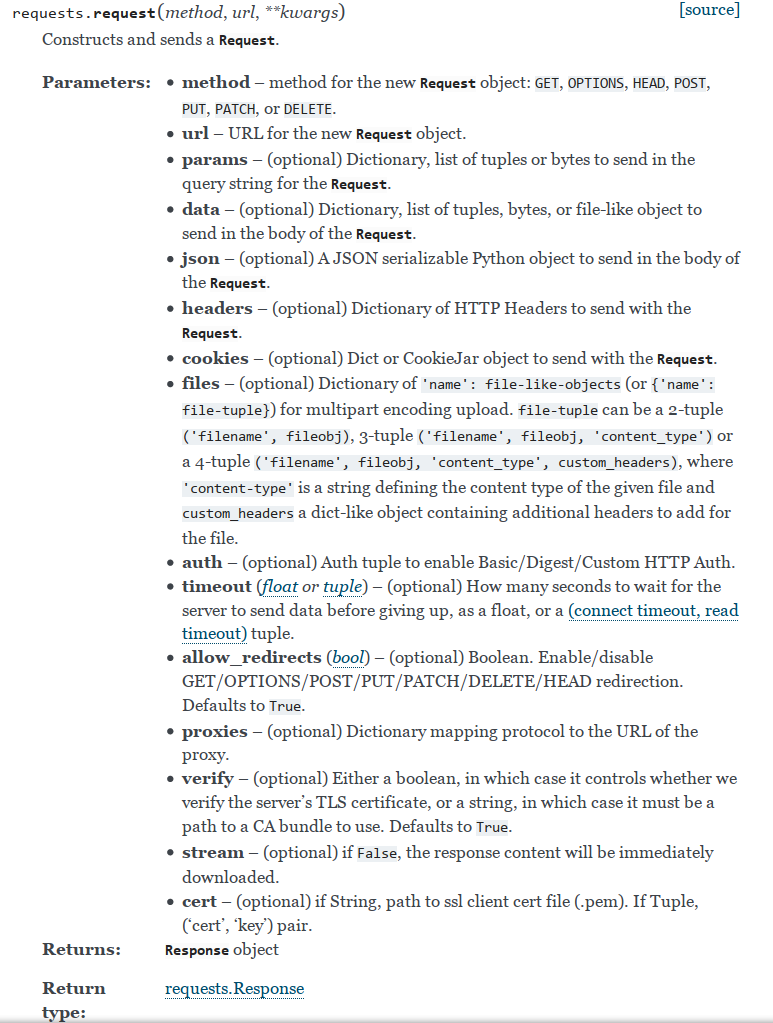

If we click Developer Interface, we get an unreadable blob of text.

Why is this unreadable?

- First of all, format. There is no easy way to distinguish between things, as everything is the same black color and bold is overused. The page is 40% blank to the sides and there is a mostly useless navigation sidebar that uses another 15% of the screen estate. Meaning that each function needs a whole page to show its parameters (this screenshot was taken on a 1920x1200 monitor, I pity the 1080p plebs…).

- Also, content. Classes, functions and everything else are intermingled in the same page.

- There are no increasingly complex examples for the functions that have many parameters.

- Trust me, I could keep ranting forever. For example, I want to read the description of what a parameter does after I have read its name and think it is useful to me, but this format does not help me at all.

At this point, this page is essentially a glorified .docx document made by the government.

Back to Advanced usage. We can find what we want as examples. Ctrl+f on the main page and search for “SSL” (SSL Cert Verification). And we get what we want.

You know why we found what we want? It is because we are doing something that happened to exist in the examples… But documentation by examples does not scale. If you happen to need to combine a couple of things, you are SOL.

Ruby

Let’s see what Ruby does. Well, I am cheating. Ruby has net/http in its standard library. Although, I’ll be honest, net/http is not the best example of a library that does HTTP requests (at least, I have personally been frustrated by it in the past). But, we are talking about documentation, not language, and you can probably find a better third party library anyway.

Large page. Ctrl+f “SSL”, we get an example. No verification. If we Ctrl+f “verify”, we see something called verify_mode. This is an attribute of … something. It’s ugly. Well, we are reading the documentation of a single class, so we can hope that this is an attribute of the Net::HTTP class. Let’s try it…

>> require 'net/http'

=> true

>> https = Net::HTTP::new('https://example.com')

=> #<Net::HTTP https://example.com:80 open=false>

>> https.verify_mode = false

=> false

Fun fact: if I hypothetically wrote https.verify = false by mistake, irb would politely ask me if I meant verify_mode. I may or may not have done that.

Rust

Finally, Rust. Let’s see the documentation of reqwest. Probably not named request because of name squatting, but let’s not digress. It might not be the best library for the job, and I haven’t made a serious effort to find the best one. Unfortunately, when it comes to the web, there are many libraries in Rust that do almost the same thing. Some support async, some support threads, some support both… Welp, I digressed :)

Notice that the documentation page is similar to the standard library. You can almost read the words “DON’T PANIC” in large, friendly letters. The page invites you to read it.

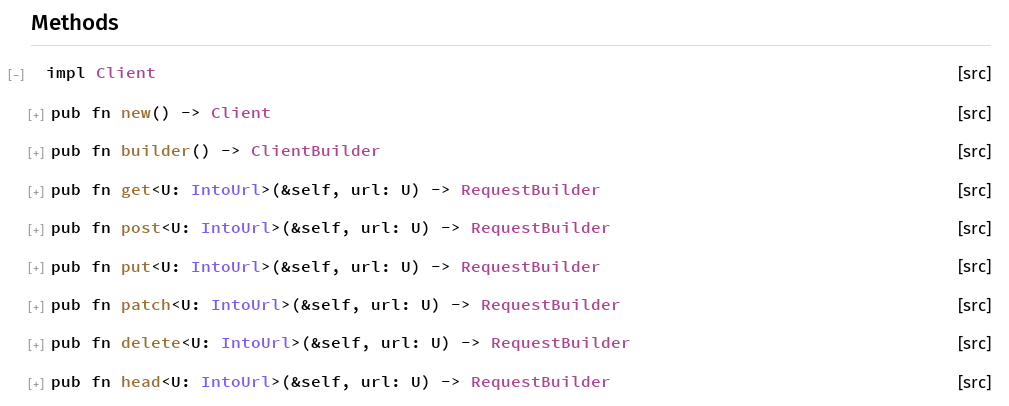

There are many ways to find what we want. In the first line, we see a Client struct. Let’s open it!

In the Client struct page, let’s press the [-] button and read the method names:

There are a bunch of methods that return a RequestBuilder and a method (static method for OOP guys) called builder that returns a ClientBuilder.

The ClientBuilder has a method called danger_accept_invalid_certs (bonus points for the name!). And we are done! The only thing we need to worry is if we will write:

let client = Client::builder()

.danger_accept_invalid_certs(true)

.build();

or

let client =

Client::builder()

.danger_accept_invalid_certs(true)

.build();

Third Example: Webservice

Let’s write a webservice! (Millions Hundreds Tens of Rustaceans are shivering right now :) ). Ok, let’s not actually write a webservice. Let’s say we inherited a webservice from an IT guy who ragequitted from his job, and we need to add support for authentication with a custom token. Let’s get a token from my favorite token generator and add an if statement to each request.

It seems our lucky numbers today are 9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725!!

Some coworkers told me that the state of the art microframework for Python is fastapi. I could equally use flask, but let’s go with fastapi. So let’s say I inherited this software:

from fastapi import FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root():

return {"Hello": "World"}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

def read_item(item_id: int, q: str = None):

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

Let’s check the documentation! Fastapi is lightning fast! It is fast to run, fast to code, good for your whole family! Ok, let’s click documentation. Oh, ok, it takes us to the same page. We just got royally trolled.

Well, let’s see the actual page:

There is a large logo. There are two useless sidebars. No API documentation, just opinions, examples, more examples, and guides. You might notice something called “Interactive API docs” and “Alternative API docs” in the sidebar; fastapi generates API documentation automatically from your API (which is a really neat feature I miss from other microframeworks - but not the point of this blog post). Imagine searching for the API documentation of something that generates API documentation.

I will state my point again. Tutorials are not documentation. They help to understand concepts the first time. Each other time they are mostly useless. What a good documentation should consist of is classes and the methods they support (or modules, functions, typeclasses and monads for functional guys). Let’s say I have a codebase and hover over a variable on my IDE, and see that it is of Foo class, can I find what to do with this class? Finally, tutorials cannot be automatically generated, so, while they require a lot of effort to generate (which is commendable!), they can never be complete with newest versions.

Anyway, knowing that most microframeworks share the same keywords, let’s search for something called a “middleware”. Ctrl+f doesn’t work. And not a single search bar in sight. Since I am impatient, I will ddg/google it directly.

Or not. This is a page with examples. No class definition, no method definitions. I don’t want to read what a middleware is, I already know it.

At this point, let’s just pray to the Python gods and blindly trust the example…

@app.middleware("http")

async def check_auth(request: Request, call_next):

if request.headers["X-TOKEN"] == '9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725':

return await call_next(request)

else:

raise NotImplementedError # TODO 403 page

Ok, After further googling, the 403 page is easy: raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Duuuude the token!")! Of course, again by a random example.

Or not. I again forgot this is Python and not Ruby, and indexing out of bounds throws an exception instead of returning nil. Multilingual guys’ problems!

@app.middleware("http")

async def check_auth(request: Request, call_next):

if request.headers.get("X-TOKEN", '') == '9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725':

return await call_next(request)

else:

raise HTTPException(status_code=403, detail="Duuuude the token!")

Except… It doesn’t work.

At this point I must interject: In no way do I bash this specific library. I know how hard it is to maintain a public library, and that is the reason I maintain none. This post is about culture differences of programming languages, not differences between libraries.

I firmly believe there is a valid reason this doesn’t work. I honestly believe I am doing it wrong. And, by searching yourself, you can convince yourself that I indeed am doing it wrong. The problem is neither the framework, nor the effort to write its documentation (which indeed shows a lot of effort and dedication). The issue lies within Python itself, and how it promotes documentation.

Long story short, the following works.

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request

from starlette.responses import JSONResponse

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root():

return {"Hello": "World"}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

def read_item(item_id: int, q: str = None):

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

@app.middleware("http")

async def check_auth(request: Request, call_next):

if request.headers.get("X-TOKEN", '') == '9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725':

return await call_next(request)

else:

return JSONResponse({"message": "duuude the token"}, status_code=403)

Maybe it still is the wrong way to do things, since fastapi has other facilities for auth, found by searching the documentation in depth (again, by reading examples).

I will try to explain my frustration. I had to read github issues, blog posts, stackoverflow posts and documentation of other libraries to make it work. It wasn’t that hard, but I shouldn’t have to do that. Imagine if this was not a widely used library but a domain-specific library like CPLEX, with no blog posts, no stackoverflow entries, nothing…

Let’s go to Ruby. We will check Sinatra, since it has a nice name. Let’s put our favorite vinyl to listen to, and get to work!

Let’s say we inherited the example in the front page:

require 'sinatra'

get '/frank-says' do

'Put this in your pipe & smoke it!'

end

Well, it takes us a while to go from the front page of sinatra to its documentation, but the domain is sinatrarb.com, so that is to be expected. Sinatra documentation has again a large blob of text, with a very different style than the standard library. But this is a Readme file. There is a sidebar with each class. We can click a class and find the methods it supports!

But the enthusiasm fades really fast. After some ctrl+f we find out that we need to search for rack middlewares. And after searching for “rack middleware”, we end up with a bunch of Ruby on Rails blogposts - surprise surprise. And rack documentation does not help, it just tells us about standard middlewares, not how to write a new middleware.

So, we find the answer in a blogpost. Or not. It took me many furious searches, and using the handy p function of Ruby to understand the contents of each variable. And I wrote the following, which works:

require 'sinatra'

require 'rack'

require 'json'

class Authenticator

def initialize(app)

@app = app

end

def call(env)

if env['HTTP_X_TOKEN'] == '9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725'

@app.call(env)

else

Rack::Response.new(JSON.pretty_generate({"message": "duuude the token"}), 403, {}).finish

end

end

end

use Authenticator

get '/frank-says' do

'Put this in your pipe & smoke it!'

end

Ruby did not win. I call this a fail. I only found the answer because a) of a third party and b) because I am more adept at Ruby than Python. This might show the awesomeness of the community… but not the documentation, which was the point to begin with.

Finally Rust. Now this is a friendly documentation template! We have your Apps, Routes, and an HttpServer! Just. ***. Kidding. Actix-web is probably the most difficult library you will ever use. It is very optimized (to the point of unsafety - there have been multiple dramas about this library, you can search them yourself), so expect heavy usage of async, which is a PITA in Rust (but for good reason).

Let’s say we inherited the example:

use actix_web::{web, App, Responder, HttpServer};

async fn index(info: web::Path<(String, u32)>) -> impl Responder {

format!("Hello {}! id:{}", info.0, info.1)

}

#[actix_rt::main]

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

HttpServer::new(|| App::new().service(

web::resource("/{name}/{id}/index.html").to(index))

)

.bind("127.0.0.1:8080")?

.run()

.await

}

Let’s search for middlewares. Wow! There is a middleware module! Let’s open that. Bummer, no examples. But let’s open the middleware called Logger. It has the following example:

use actix_web::middleware::Logger;

use actix_web::App;

fn main() {

std::env::set_var("RUST_LOG", "actix_web=info");

env_logger::init();

let app = App::new()

.wrap(Logger::default())

.wrap(Logger::new("%a %{User-Agent}i"));

}

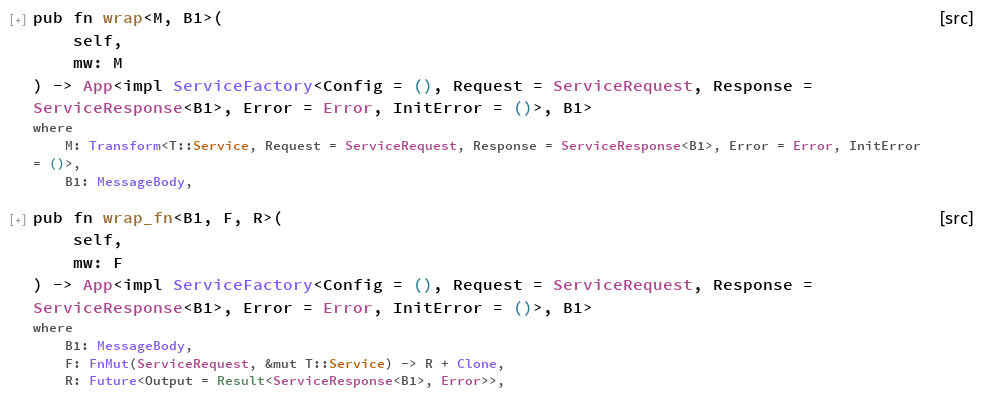

By reading the example, it seems that middlewares are registered by using the wrap method of an App.

Let’s go back to the App.

Welp. This looks scary. But that wrap_fn method seems to take a friendly FnMut(ServiceRequest, &mut T::Service) -> R + Clone function instead of a scary datatype that implements the Transform<T::Service, Request = ServiceRequest, Response = ServiceResponse<B1>, Error = Error, InitError = ()> trait.

This friendly function takes a function that expects a ServiceRequest (?) and a T::Service (??), where T is the generic parameter of the App (???). Ok, it makes no sense. BUT! When all fail, we can expand the definition and read the example:

use actix_service::Service;

use actix_web::{web, App};

use actix_web::http::{header::CONTENT_TYPE, HeaderValue};

async fn index() -> &'static str {

"Welcome!"

}

fn main() {

let app = App::new()

.wrap_fn(|req, srv| {

let fut = srv.call(req);

async {

let mut res = fut.await?;

res.headers_mut().insert(

CONTENT_TYPE, HeaderValue::from_static("text/plain"),

);

Ok(res)

}

})

.route("/index.html", web::get().to(index));

}

So, we propagate calls by calling the call method of the srv, passing req as the argument. And we get the response by awaiting the future.

Let’s click the Request to see its methods. It has a method called headers. Let’s click HeaderMap. It says it is a multimap with methods such as get. No example, so we need to also click HeaderName. It seems that something like req.headers().get(HeaderName::from_static("X-TOKEN")) should work. (Spoiler, it won’t. If we read the documentation carefully, we will notice that "x-token" needs to be lowercase).

Now, let’s go to the main page of the documentation. There is a module called error. If we open it, we find a struct named ErrorForbidden, with a new method that accepts something that is Debug + Display + 'static. Something like a &'static str, or a string literal for everyone else :)

Finally, let’s put the pieces of the puzzle together:

use actix_web::{web, App, Responder, HttpServer, error::ErrorForbidden};

use actix_service::Service;

use actix_web::http::HeaderName;

async fn index(info: web::Path<(String, u32)>) -> impl Responder {

format!("Hello {}! id:{}", info.0, info.1)

}

#[actix_rt::main]

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

HttpServer::new(||

App::new()

.wrap_fn(|req, srv| {

let mut fut = None;

if let Some(token) = req.headers().get(HeaderName::from_static("x-token")) {

if token == "9ee519f0-33b1-46bb-a53c-24670b161725" {

fut = Some(srv.call(req));

}

}

async {

match fut {

Some(future) => Ok(future.await?),

None => Err(ErrorForbidden("\"message\": \"the token duuude\""))

}

}

})

.service(web::resource("/{name}/{id}/index.html").to(index))

)

.bind("127.0.0.1:8080")?

.run()

.await

}

I won’t lie to you. It wasn’t easy. And I probably did it because I know how to program defensively in Rust, in order to avoid being yelled at by the type checker and the borrow checker. But we are talking about async Rust here! It was difficult because Rust is a difficult language, not because of the documentation. I can’t help but admire the fact that I never left the documentation. No stackoverflow, nothing. (Well, even if I did, you can rarely find answers about async Rust in the interwebs ^^)

So, what is the conclusion? Nothing actionable. The problem is not the unwillingness of library developers to write proper documentation; it is the tooling. We should acknowledge that documentation is part of the language design. Docs.rs is a godsend. Maybe other languages should try to have a dedicated documentation server that builds all documentation automatically (from all libraries residing in pypi and rubygems), produces the same style and enforces the same format.

Or maybe not. Maybe I am overreacting and this is not needed for the far simpler languages such as Python and Ruby. After all, my examples finally worked, didn’t they? :)